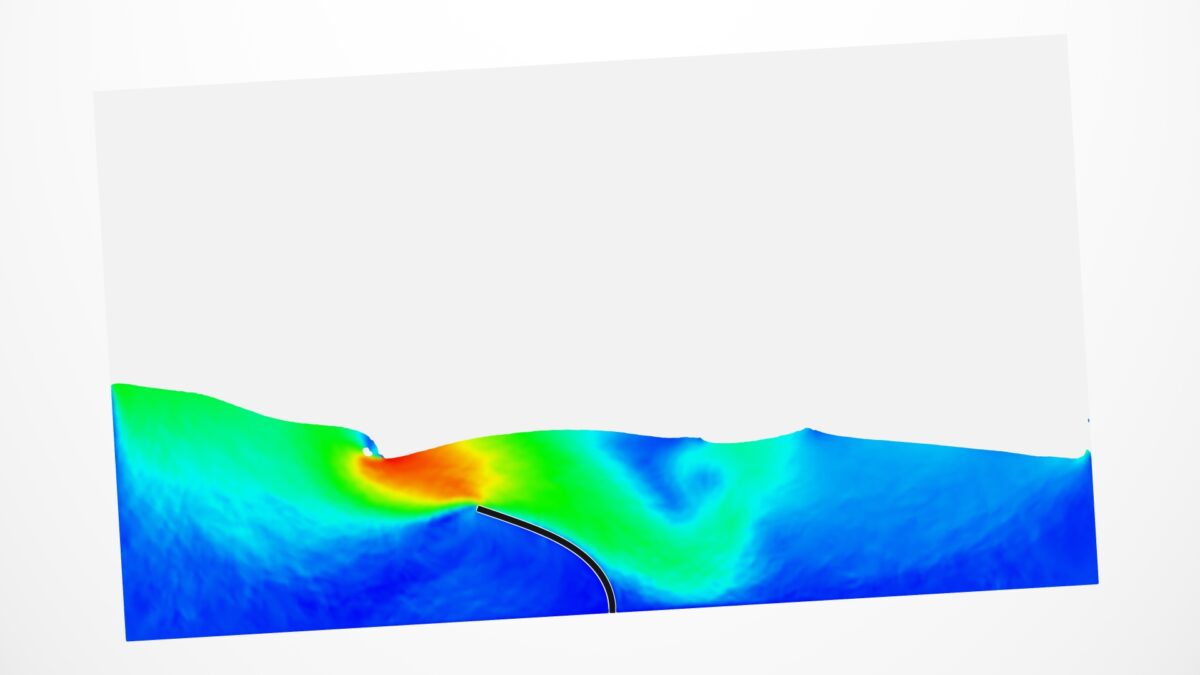

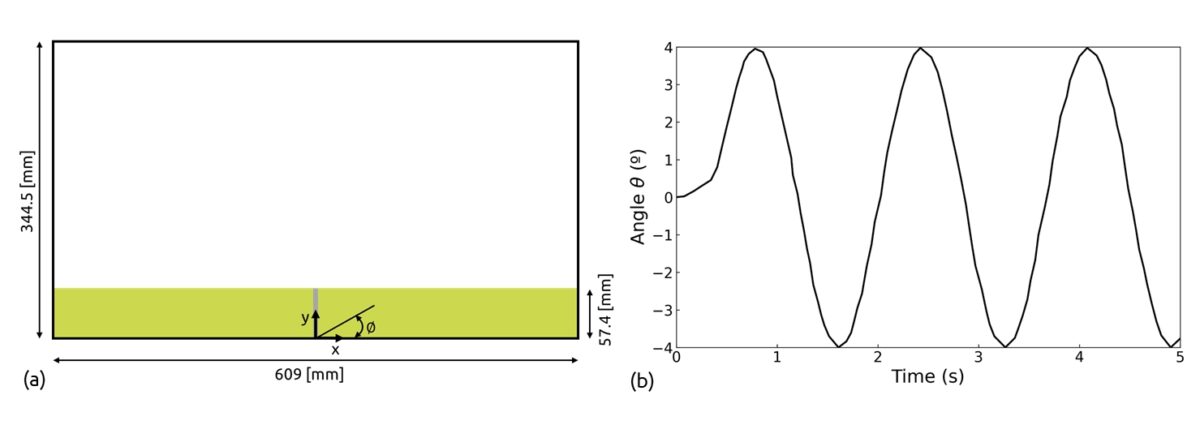

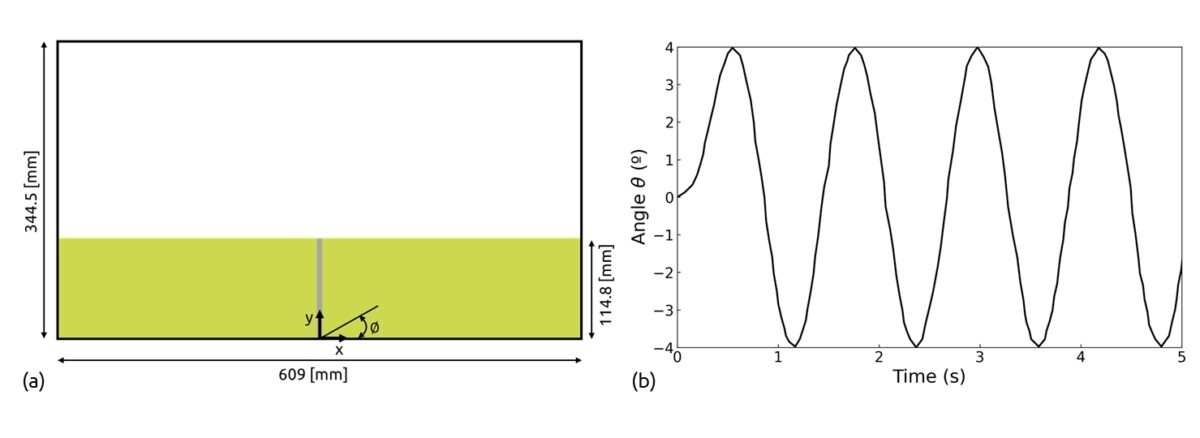

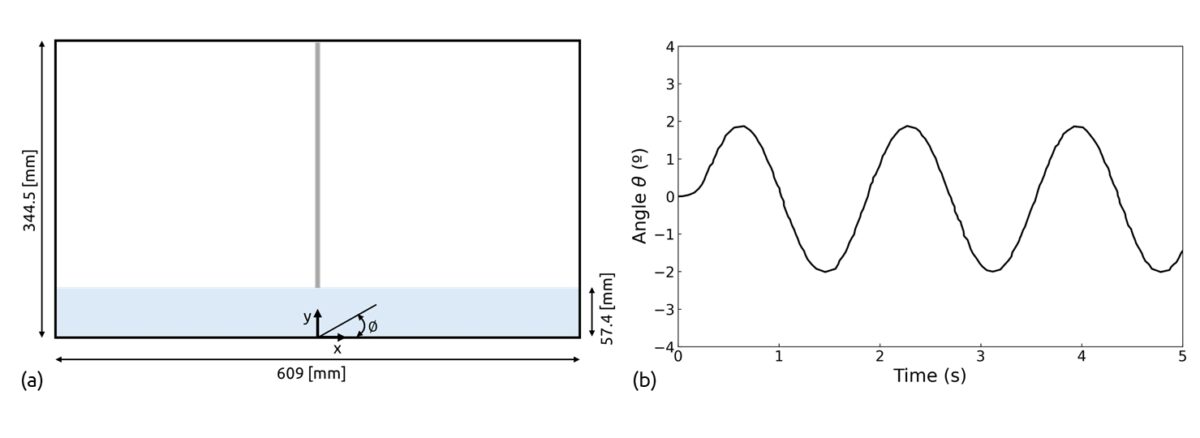

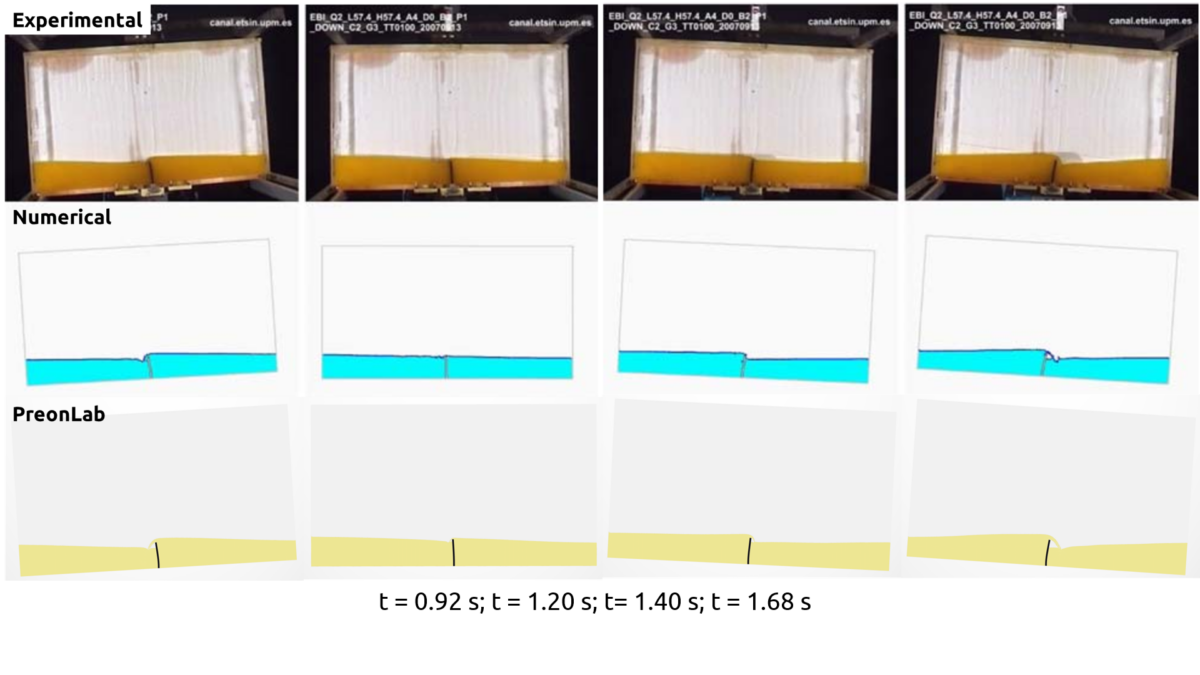

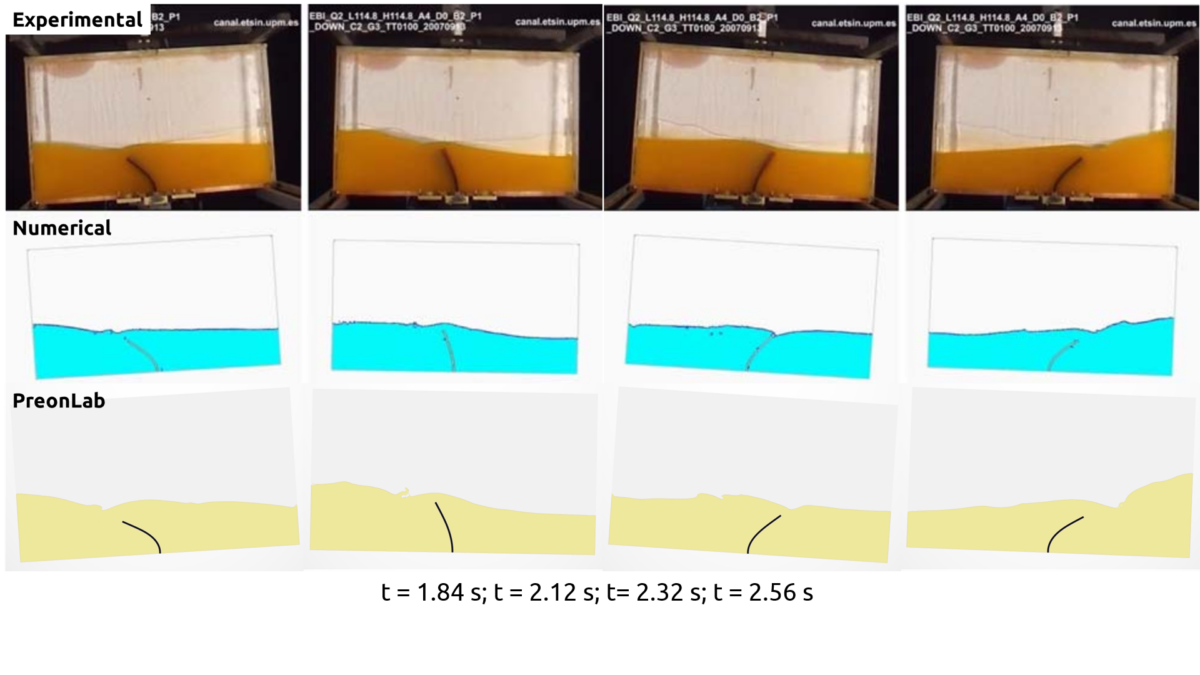

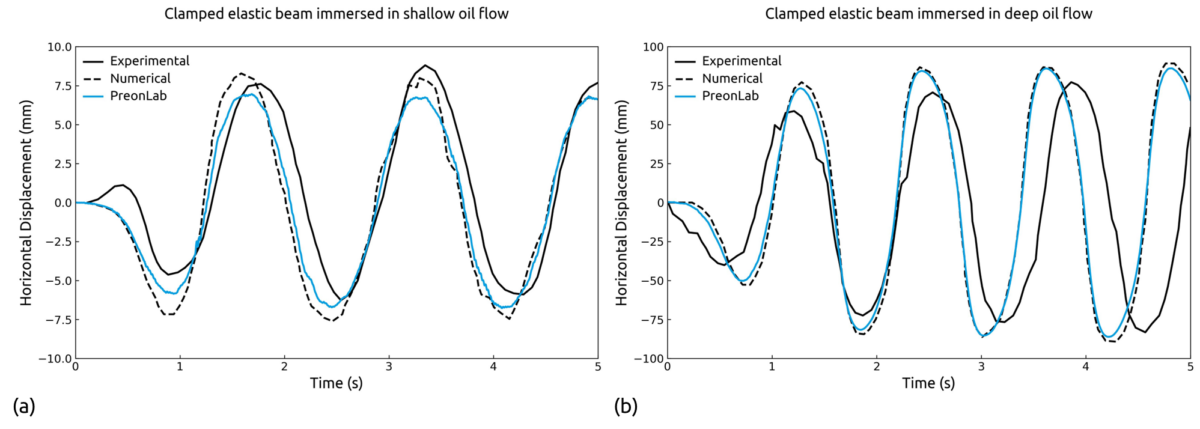

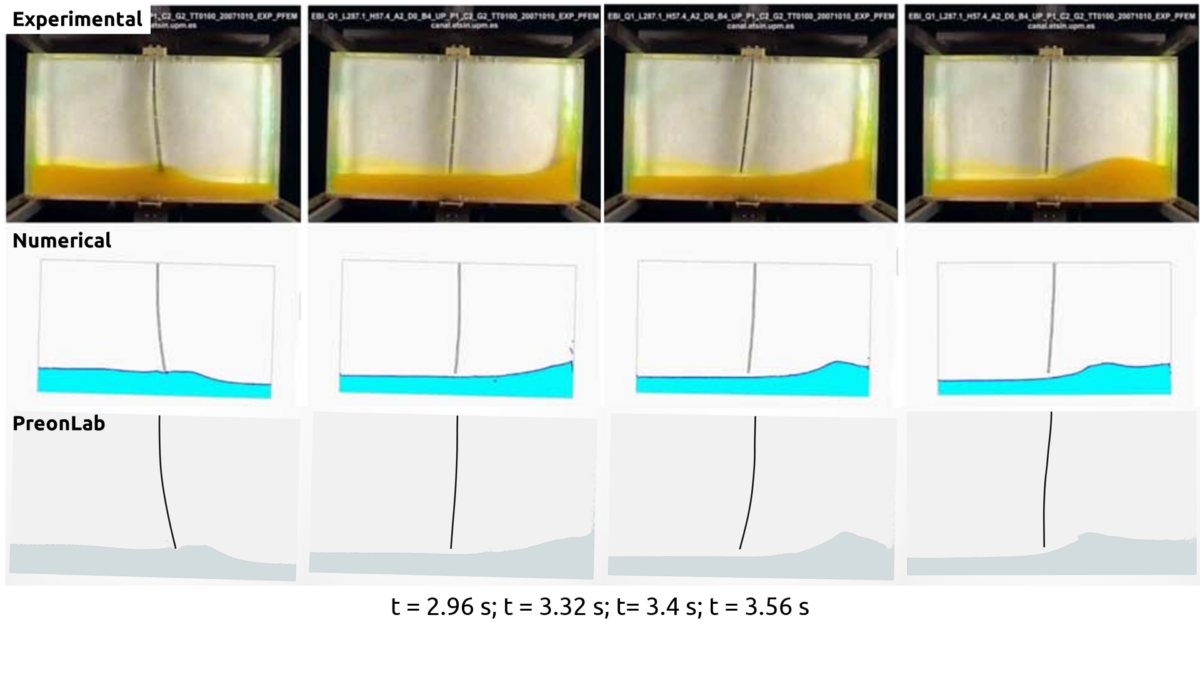

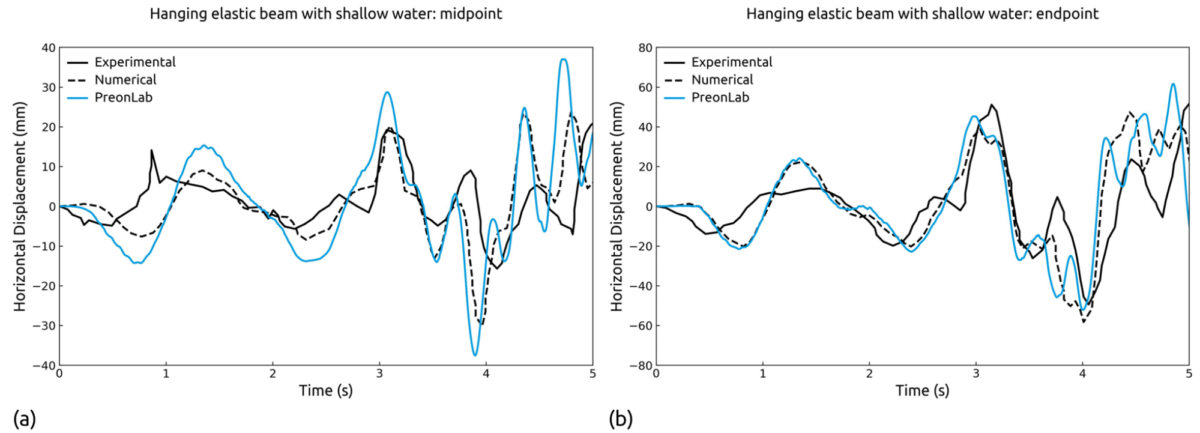

FSI involves the interaction between fluid and solid domains, where the motion and forces in one domain influence the other, and vice versa. In many real-world scenarios, fluid flows interact with deformable solid bodies. While the deformation of these solid bodies is typically minimal and can be neglected in most simulations, there are cases where this interaction becomes significant. For instance, in a soiling simulation, the deformation of components like mudflaps can influence the behavior of the fluid. Another case is the movement of windshield wipers interacting with rainwater. In this scenario, the deformation of the wiper blades plays a significant role and can influence simulation results. Figure 1 shows the velocity field in a sloshing tank with a flexible beam simulation, where such fluid and solid interaction is considered. The simulation has been performed in PreonLab 6.2.

Smoothed Particle Hydrodynamics (SPH) has become one of the most popular methods for modeling free-surface flows. With its Lagrangian formulation and mesh-free method, SPH has an advantage over other computational methods in solving simulations with large fluid deformations, complex geometries, and dynamic interfaces. The inherent advantages of the SPH method, coupled with a strong focus on usability, make PreonLab a powerful, reliable and user-friendly simulation tool.

With the introduction of the linear elastic solver, PreonLab leverages the potential of the SPH method and the Lagrangian formulation to build a more capable tool in terms of multiphysics. However, the implementation of a linear elastic solver is not straightforward and presents several challenges. For instance, as SPH is naturally suited to problems involving large strains and deformations, it often requires enhanced formulations or specialized kernel functions to ensure accuracy in small deformation problems. Additionally, modeling rotation poses its own set of challenges, as discussed by Peer et al. [2]. Despite these challenges, the SPH-based FSI implementation in PreonLab offers notable advantages. One of the key benefits is its mesh-free interface handling, which eliminates the need for mesh element alignment at the fluid-solid interface, unlike traditional methods. This flexibility is especially valuable for simulating large deformations and highly dynamic interfaces.

In PreonLab 6.2, FSI problems are solved as a combined system, meaning that the fluid and elastic subproblems are solved within a single framework. This allows for more accurate and stable interaction between the two phases, as it avoids potential issues related to partitioned solvers that treat the fluid and solid phases separately. PreonLab 6.2 introduces a solver capable of modeling linear elastic solids on their own, or in a coupled multiphysics FSI context.